Overview

What is Celiac Disease?

Celiac disease is a chronic autoimmune disorder that affects approximately 1% of the global population, though many cases remain undiagnosed. This condition occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks the small intestine in response to consuming gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley, rye, and their derivatives. Unlike a simple food allergy or intolerance, celiac disease involves a complex immune response that can cause significant damage to the intestinal lining over time.

The condition was first described in ancient times, but it wasn’t until the 1940s that Dutch pediatrician Dr. Willem Dicke discovered the connection between wheat consumption and symptoms. Today, celiac disease is recognized as a serious medical condition that requires lifelong dietary management and regular medical monitoring.

How Does It Affect the Body?

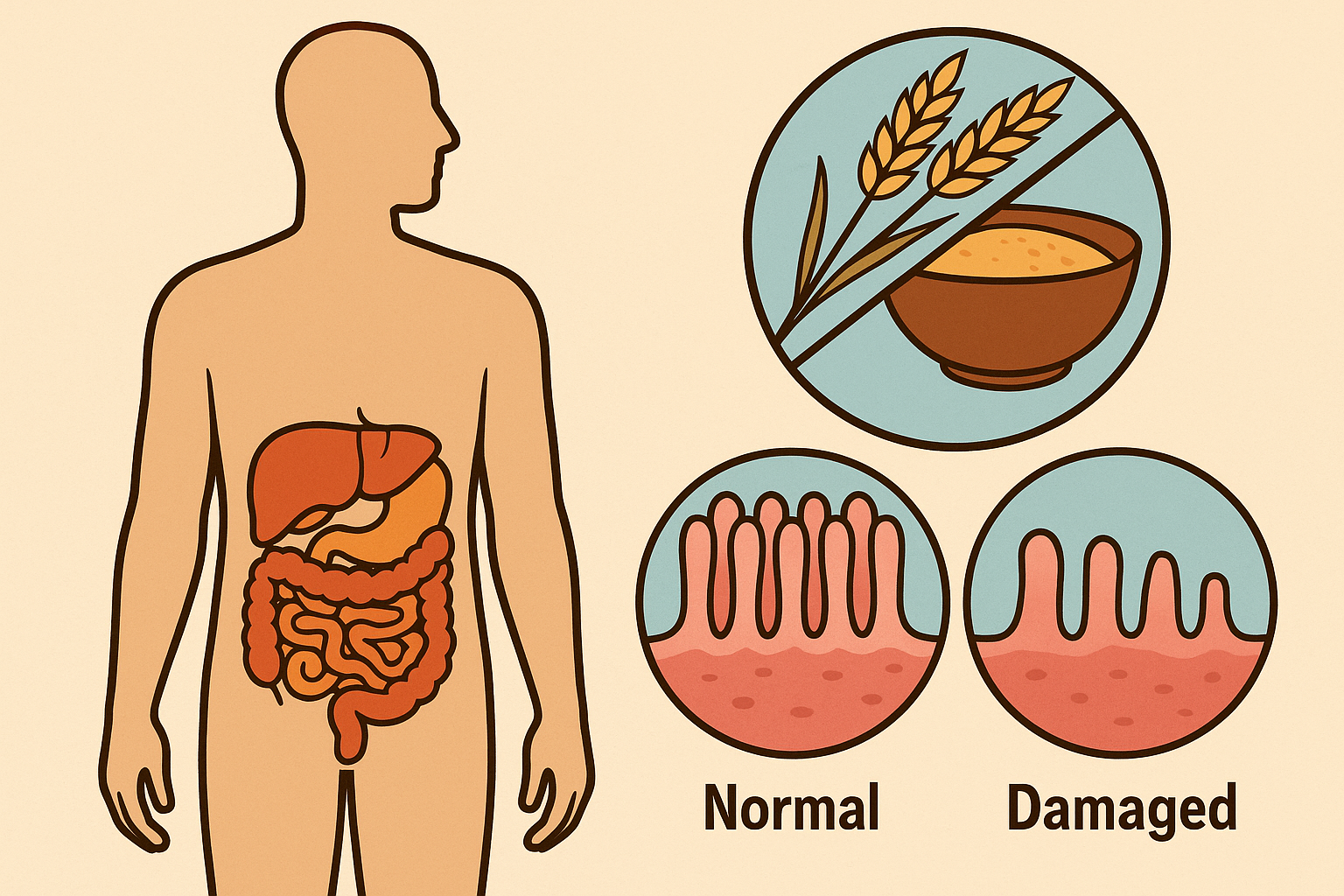

When individuals with celiac disease consume gluten, their immune system launches an inflammatory response that targets the villi—tiny, finger-like projections lining the small intestine. These villi are crucial for nutrient absorption, as they dramatically increase the surface area available for absorbing vitamins, minerals, and other essential nutrients from food.

The autoimmune attack gradually flattens and destroys these villi, a process called villous atrophy. This damage significantly reduces the intestine’s ability to absorb nutrients, leading to malabsorption and a cascade of health problems. The inflammation can also affect other parts of the digestive system and trigger systemic effects throughout the body.

The severity of intestinal damage varies among individuals and depends on factors such as genetic predisposition, age at first exposure to gluten, duration of gluten consumption, and individual immune system responses. Some people may have mild villous blunting, while others experience complete villous atrophy.

Causes & Risk Factors

What Causes Celiac Disease?

Celiac disease results from a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and immunological factors. The condition requires specific genetic markers to develop, but genetics alone don’t determine who will develop the disease. Environmental triggers and immune system dysfunction also play crucial roles.

The primary environmental trigger is gluten exposure, but other factors may influence disease development, including infections (particularly rotavirus in early childhood), stress, pregnancy, surgery, and certain medications. Some research suggests that the timing of gluten introduction in infancy and breastfeeding duration may also influence celiac disease risk.

What is the Main Cause of Celiac Disease?

A person’s genes, combined with eating foods with gluten and other factors, can contribute to celiac disease. However, the precise cause isn’t known. Two specific genes, HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8, are present in virtually all people with celiac disease (about 97% of diagnosed cases). These genes produce proteins that present gluten fragments to immune cells, triggering an inflammatory cascade.

However, having these genes doesn’t guarantee celiac disease development. Approximately 30-40% of the general population carries these genetic markers, but only a small percentage of those individuals ever develop celiac disease. This suggests that additional genetic factors and environmental triggers are necessary for the condition to manifest, though the exact mechanisms remain unclear.

The immune system’s response involves both innate and adaptive immunity. When gluten is consumed, the enzyme tissue transglutaminase modifies gluten proteins, making them more likely to trigger immune responses. The immune system then produces antibodies against both gluten and the body’s own tissues, leading to the characteristic intestinal damage and systemic symptoms.

Symptoms

Adults vs Children Symptoms

Celiac disease symptoms can vary dramatically between adults and children, and even among individuals within the same age group. This variability often leads to delayed diagnosis and prolonged suffering.

In children, classic symptoms typically include chronic diarrhea, abdominal bloating, failure to thrive, delayed growth, and irritability. Children may also experience dental enamel defects, delayed puberty, and behavioral problems. Infants might show symptoms shortly after gluten introduction, including vomiting, distended abdomen, and poor weight gain.

Adult symptoms are often more subtle and may not primarily involve the digestive system. Many adults experience what’s called “non-classical” celiac disease, with symptoms such as chronic fatigue, depression, anxiety, headaches, joint pain, bone loss, and anemia. Some adults may have iron-deficiency anemia as their only presenting symptom.

Interestingly, some individuals have “silent” celiac disease, where intestinal damage occurs without obvious symptoms. These cases are often discovered during family screening or when investigating other autoimmune conditions.

Skin-Related Symptoms

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is a distinctive skin manifestation of celiac disease, affecting approximately 10-25% of people with the condition. This chronic, intensely itchy rash typically appears on the elbows, knees, buttocks, back, and scalp. The rash consists of small, clustered blisters that are often scratched away before medical examination, leaving only excoriation marks.

Other skin-related symptoms may include general itchiness, eczema-like rashes, hair loss (alopecia areata), and poor wound healing. Some individuals experience chronic urticaria (hives) or other unexplained skin conditions that improve with gluten-free diet implementation.

The skin symptoms in celiac disease result from the same autoimmune process affecting the intestine. Antibodies deposit in skin tissue, causing inflammation and the characteristic rash pattern. Dermatitis herpetiformis often responds to strict gluten-free diet adherence, though improvement may take months to years.

Diagnosis

Blood Tests, Endoscopy, Genetic Tests

Diagnosing celiac disease requires a systematic approach combining clinical evaluation, laboratory testing, and often tissue examination. The diagnostic process typically begins while the patient is still consuming gluten, as gluten-free diets can normalize test results and make diagnosis difficult.

Blood tests form the initial screening step and measure specific antibodies produced in response to gluten exposure. The most commonly used tests include tissue transglutaminase antibodies (tTG-IgA), endomysial antibodies (EMA-IgA), and deamidated gliadin peptide antibodies (DGP-IgG and DGP-IgA). Total IgA levels are also measured, as IgA deficiency can cause false-negative results in approximately 2-3% of celiac patients.

Genetic testing identifies the presence of HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 genes. While positive genetic tests don’t confirm celiac disease, negative results can effectively rule out the condition, as celiac disease is extremely rare in their absence. Genetic testing is particularly useful for family screening and in cases where other tests are inconclusive.

Endoscopy with small intestinal biopsy remains the gold standard for celiac disease diagnosis in many cases. During this procedure, a flexible tube with a camera is passed through the mouth to examine the small intestine directly. Multiple tissue samples are taken from different areas and examined under a microscope for characteristic damage patterns, including villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and increased inflammatory cells.

Treatment / Management

Gluten-Free Diet Basics

The cornerstone of celiac disease management is strict, lifelong adherence to a gluten-free diet. This means completely eliminating wheat, barley, rye, and all their derivatives from the diet. Even tiny amounts of gluten can trigger immune responses and prevent intestinal healing in sensitive individuals.

Reading food labels becomes essential, as gluten can hide in unexpected products including sauces, seasonings, medications, and even cosmetics that might be accidentally ingested. Foods labeled as “wheat-free” are not necessarily gluten-free, and terms like “modified food starch” may indicate gluten-containing ingredients.

Safe grains and starches include rice, corn, quinoa, amaranth, buckwheat, millet, and certified gluten-free oats. However, cross-contamination during processing is a significant concern, making certified gluten-free products important for many individuals.

The learning curve for gluten-free living can be steep, requiring education about safe foods, cooking techniques, and dining out strategies. Many people benefit from working with registered dietitians specializing in celiac disease to ensure nutritional adequacy and proper implementation of the gluten-free diet.

What Can’t Celiacs Eat?

People with celiac disease must avoid all foods containing gluten, which means eliminating wheat (including farina, semolina, durum, bulgur, spelt, emmer, couscous, and Kamut), barley (and malt made from barley), and rye from their diet. This includes obvious sources like bread, pasta, pizza, beer, and baked goods made with these grains.

However, gluten lurks in many unexpected places, making vigilance essential. Processed foods often contain gluten as thickeners, stabilizers, or flavor enhancers. Common hidden sources include soups and sauces, dressings and condiments, processed meats like hot dogs and deli meats, processed cheese and yogurt products, packaged dinners, and sweets. Even small amounts of gluten, such as a spoonful of pasta, can cause very unpleasant intestinal symptoms in people with celiac disease.

Restaurant dining requires careful communication with staff about preparation methods and ingredients. Shared fryers, grills, and preparation surfaces can introduce gluten into otherwise safe foods. Many restaurants now offer gluten-free menus, but the level of cross-contamination prevention varies significantly.

Some individuals with celiac disease also need to avoid oats, even gluten-free varieties, as a small percentage react to avenin, a protein in oats similar to gluten. Additionally, some people develop temporary or permanent intolerances to other foods, particularly dairy products, during the healing phase.

Supplements and Nutrition Tips

Newly diagnosed celiac disease patients often have multiple nutritional deficiencies due to prolonged malabsorption. Common deficiencies include iron, B vitamins (especially B12 and folate), vitamin D, calcium, and zinc. Comprehensive nutritional assessment and appropriate supplementation are crucial for optimal recovery.

Gluten-free diets can be naturally low in fiber, B vitamins, and iron while being higher in fat and sugar than regular diets. Choosing nutrient-dense, naturally gluten-free whole foods over processed gluten-free products helps optimize nutrition. Incorporating a variety of gluten-free grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, fruits, and vegetables ensures adequate nutrient intake.

Some individuals benefit from probiotics to help restore healthy gut bacteria, though research is still evolving. Digestive enzymes might help during the initial healing phase, but they should not be considered a substitute for strict gluten-free diet adherence.

Complications

If Untreated, Long-Term Health Effects

Untreated celiac disease can lead to serious long-term health complications affecting multiple body systems. Continued gluten exposure and chronic inflammation increase the risk of developing additional autoimmune conditions, osteoporosis, infertility, neurological problems, and certain cancers.

Malabsorption of essential nutrients can result in severe anemia, bone disease, growth retardation in children, and increased fracture risk. The chronic inflammation associated with untreated celiac disease may contribute to cardiovascular disease and metabolic disorders.

What Happens If Celiac Disease Goes Untreated?

Without proper treatment through strict gluten-free diet adherence, celiac disease can progress to cause serious complications. Untreated celiac disease can lead to the development of other autoimmune disorders like type 1 diabetes and multiple sclerosis, along with many other conditions including dermatitis herpetiformis (an itchy skin rash), anemia, osteoporosis, infertility and miscarriage, and neurological conditions like epilepsy and migraines.

The most serious long-term risk is the development of intestinal lymphoma and small bowel cancer. People with celiac disease who don’t maintain a gluten-free diet have a greater risk of developing several forms of cancer. However, cancer risk appears to decrease with strict gluten-free diet adherence, emphasizing the importance of proper treatment.

Refractory celiac disease is a rare but serious complication where symptoms and intestinal damage persist despite strict gluten-free diet adherence for more than 12 months. This condition requires specialized medical management and may indicate the development of lymphoma.

Neurological complications can include peripheral neuropathy, cerebellar ataxia, seizures, and cognitive impairment. These neurological symptoms may occur even in the absence of significant gastrointestinal symptoms and can be partially reversible with gluten-free diet treatment.

Outlook / Prognosis

Lifestyle Impact

The lifestyle impact of celiac disease extends far beyond dietary changes, affecting social interactions, travel, career choices, and family dynamics. Social situations involving food can become challenging, requiring advance planning and clear communication about dietary needs.

Many people experience anxiety around food safety and cross-contamination, particularly when eating outside their controlled home environment. This can lead to social isolation if not properly managed through education, support, and gradual confidence building.

What is the Life Expectancy for Someone with Celiacs?

Most people with celiac disease will have a normal life expectancy, providing they are able to manage the condition by adhering to a lifelong gluten-free diet. With proper diagnosis and strict adherence to a gluten-free diet, people with celiac disease can expect the same life expectancy and quality of life as the general population.

However, delayed diagnosis and poor dietary adherence can impact long-term health outcomes. The key to optimal prognosis lies in early diagnosis, comprehensive education about gluten-free living, regular medical monitoring, and strong support systems. Gluten is not an essential part of your diet, so it can be safely removed and replaced with safe foods or gluten-free alternatives.

Most people experience significant improvement in symptoms within weeks to months of starting a gluten-free diet, though complete intestinal healing may take up to two years. Children typically heal faster than adults, and younger age at diagnosis generally correlates with better outcomes.

Living With

Eating Out, Traveling, Hidden Gluten Sources

Successfully managing celiac disease while maintaining an active social and professional life requires developing practical strategies for various situations. Restaurant dining becomes manageable with research, preparation, and clear communication. Many establishments now provide gluten-free menus and staff training, though vigilance remains important.

Traveling with celiac disease requires advance planning, including researching destination restaurants, packing safe snacks, and learning key phrases in foreign languages if traveling internationally. Many hotels can accommodate special dietary needs with advance notice.

Quick Lifestyle & Diet Hacks

Developing efficient systems for gluten-free living can significantly improve quality of life. Meal planning and batch cooking help ensure safe, convenient meals are always available. Maintaining a well-stocked pantry of gluten-free staples prevents last-minute food crises.

Technology can be invaluable, with smartphone apps helping identify safe foods, locate gluten-free restaurants, and connect with other celiac disease community members. Many apps allow scanning barcodes to quickly determine if products are gluten-free.

Building relationships with local suppliers, including gluten-free bakeries and specialty stores, ensures access to safe, high-quality foods. Many communities have celiac disease support groups that share resources, recipes, and moral support.

The key to successful celiac disease management lies in viewing the gluten-free lifestyle not as a restriction but as a pathway to better health. With proper education, support, and commitment, people with celiac disease can lead full, healthy, and satisfying lives while effectively managing their condition.